When Fonatur Came to Puerto Escondido

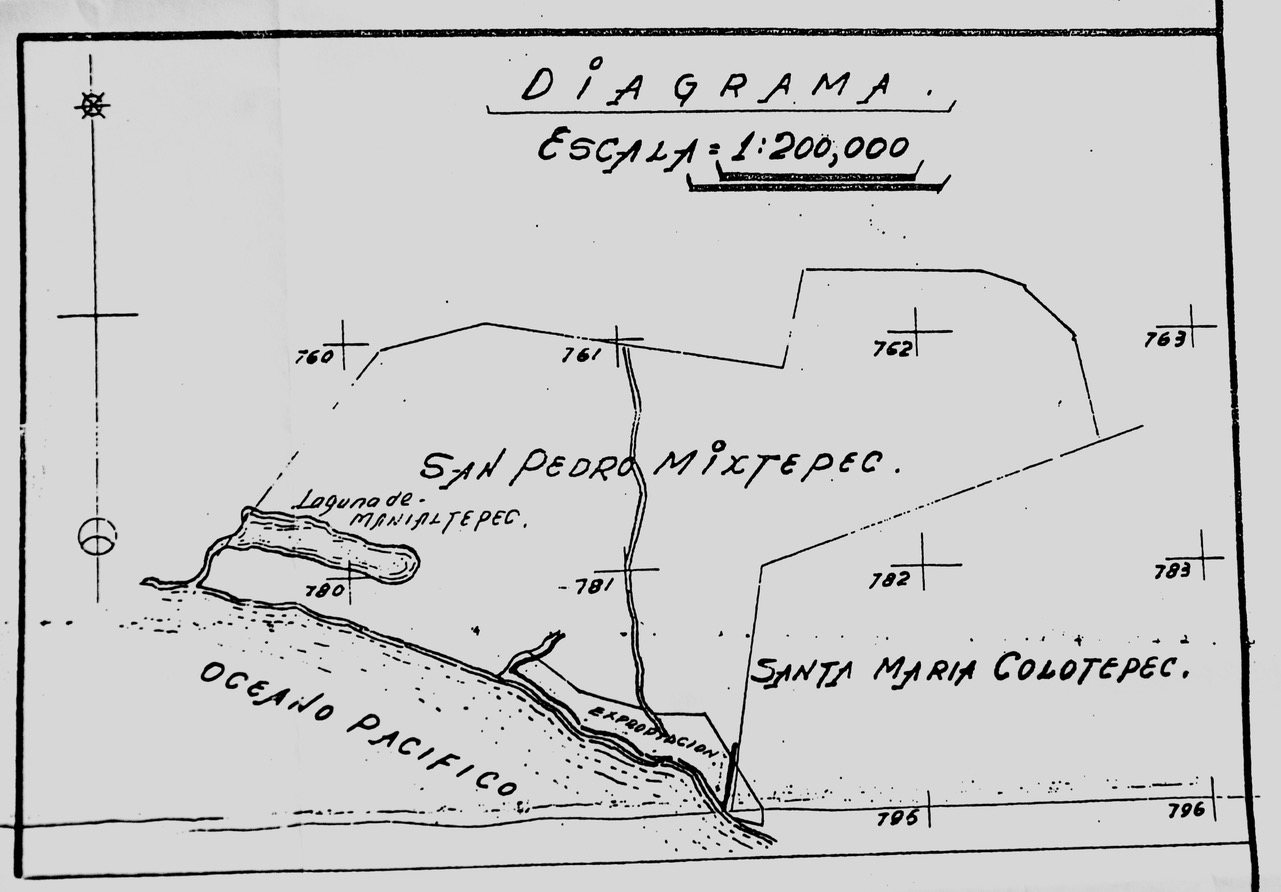

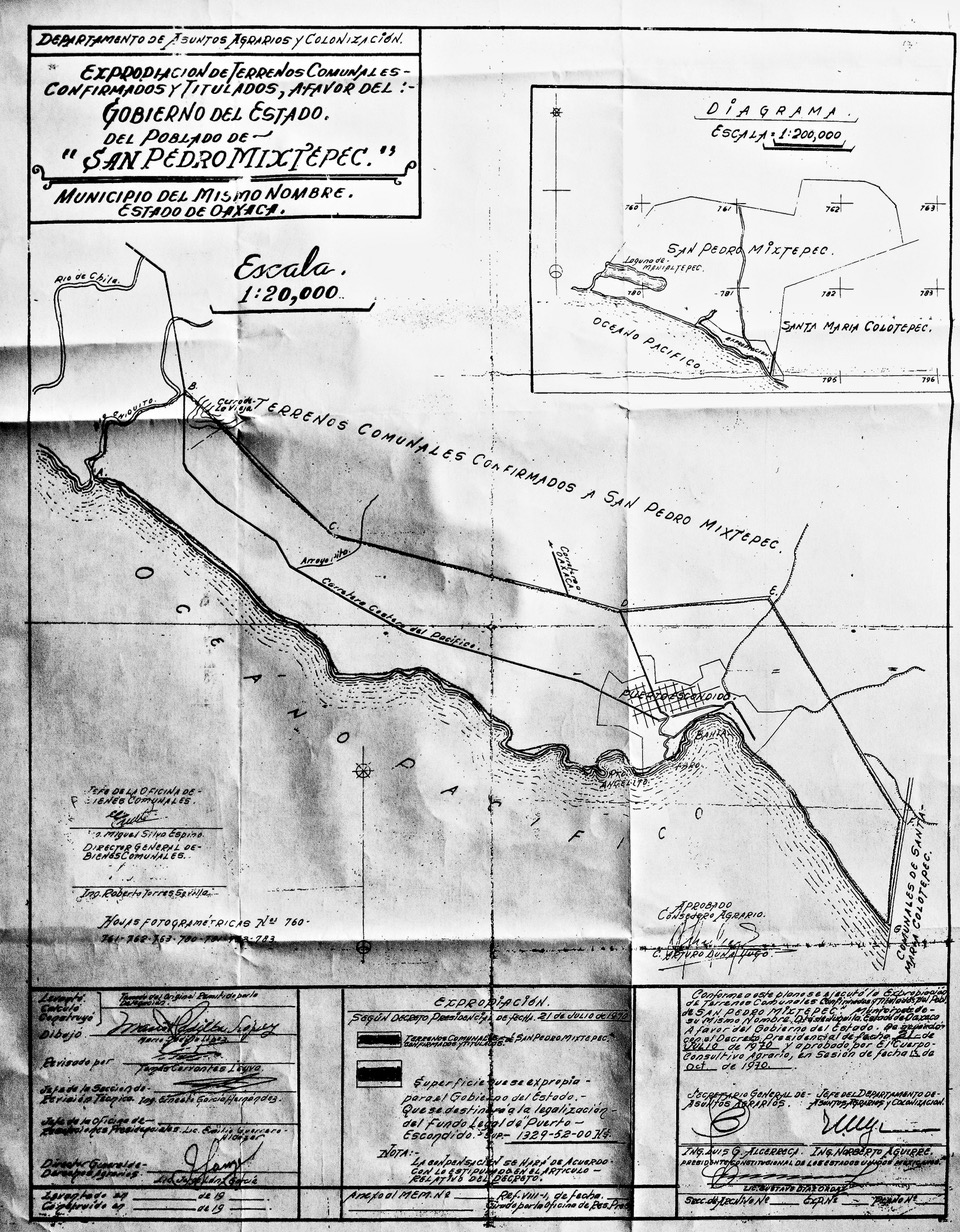

On July 21, 1970, President Díaz Ordaz signed the decree of expropriation of 1,329 hectares of Puerto Escondido, from the Punta de Zicatela to the Cerro de la Vieja (near Chila) for the purpose of creating a “tourist platform.”

This land, which had previously been communal, was now privatized, and the owners were given deeds (escrituras públicas) issued by the Fundo Legal de Puerto Escondido or FIPE (the Fideicomiso de Puerto Escondido).

The story begins in the late 1960s. Acapulco has become a major international tourist destination (think Elvis Presley in Fun in Acapulco) and Mexico wants to expand its beach tourism industry. The Bank of Mexico, with a loan from the Inter-American Development Bank, sends out two young bankers to explore all of Mexico’s coasts. The goal was to discover beautiful, undeveloped beaches that could be turned into resorts.

The explorers came up with a list of six: Loreto, Los Cabos, Zihuatanejo, Puerto Escondido, Huatulco, and Cancún. Puerto Escondido, Cancún and Zihuatanejo were the favorites And so it was that in 1970 Cancún, Ixtapa (Zihuatanejo), and Puerto Escondido were expropriated by the federal government for tourist development.

Puerto had a lot to offer: beautiful beaches, a good climate, and a population of 3,428, according to the 1970 census. Federal highway 200 had been extended in the 1960s from Acapulco to Salina Cruz. But otherwise there were no paved roads. Highway 175 was still unpaved from Miahuatlán to Pochutla, and highway 131 was a dirt road from Sola de Vega to Puerto Escondido. However, there was an airstrip on what is now the Rinconada. Zicatela, however, was virgin forest: huizache trees with long thorns and mesquites. There were jaguarundis, coyotes, rabbits, a few deer and lots of scorpions.

The Bank of Mexico financed the newly formed Fonatur (Fundo Nacional de Fomento al Turismo) which was charged with buying land and developing infrastructure (roads, airports, potable water, electricity, sewage systems etc.) In the case of Oaxaca, Fonatur worked with the State of Oaxaca through the Fundo Legal de Puerto Escondido, (later FIPE) and Fifonafe (el Fideicomiso Fondo Nacional de Fomento Ejidal) to develop the expropriated land that went from Punta Zicatela to the Cerro de La Vieja (near Chila) and as far north as calle 9a Norte where the Escuela Secundaria Técnica 86 is now located.

What went wrong? Why did Fonatur decide to abandon Puerto in 1980 and develop Huatulco instead? Contrary to local folklore, the problem was not with Colotepec, according to Rigoberto Pacheco who was the public accountant for Fonatur from 1976 to 1981. Rather, the sticking point was that the American who owned all the land on Zicatela that is now Tamarindos refused to sell. (Even when land is expropriated, it must be purchased. Then the seller is given other properties in the expropriated zone.)

Santa María Colotepec had ceded its claim to Puerto Escondido, including all of Zicatela, to San Pedro Mixtepec at a meeting with Governor Victor Bravo Ahuja in 1969 during which they were promised electricity, potable water, roads, and a health center. These projects were to be paid for by the State through the Fundo Legal de Puerto Escondido within five years. The State did not comply with the terms of the agreement, but it wasn’t until 1984 that Colotepec attempted to regain the territory. (See ¡Viva Puerto! #25.)

Don Rigo points out that Huatulco was very much Fonatur’s second choice, mainly because it is hotter than Puerto. By 1980, Fonatur had built our airport. It then consisted of one, paved, 1,600-meter, runway, just capable of handling DC 3’s and Convair propeller planes. But with donated land, Fonatur was able to extend the runway in 1984 so that it could handle jets.

And why, I asked, was Bacocho — Fonatur’s only development in Puerto — built so far from the shore? The answer was simple; investors like Robert Jones and Enrique Sada already owned beachfront properties which they planned to develop. Bacocho, however, was owned by farmers who were happy to sell. The owners of land on Playa Principal had reached an agreement with the state that allowed them to keep their expropriated properties, which explains why no big resorts were built there.

Bacocho was designed to provide housing — with electricity, potable water, and a sewage system — for the business people and professionals that a resort community needs, but its beachfront was reserved for hotels. By 1980, Fonatur had built the Hotel Viva (now the Posada Real), Puerto’s first resort hotel and Cocos Beach Club on Bacocho beach.

Fonatur’s other, unfulfilled, projects for Puerto included a golf course above Bacocho beach, a nature reserve on Punta Colorada, a hotel zone, and recreational and sports facilities.

In 1989, Governor Heladio Ramírez López recognized the municipio of Sta. María Colotepec’s claim to the land east of the Av. Oaxaca, including the Bahía Principal and Zicatela, which had previously been ceded to the municipio of San Pedro Mixtepec. The contested area is now designated a “zone of conflict”.

The Bienes Comunales of San Pedro Mixtepec has plans for developing the Chila coast. This includes a 7.5 km. boardwalk (malecón) with four access roads from the highway. There will also be a marina. Meanwhile, the struggle with Viva Resorts continues, according to Javier Cruz Jiménez, the president of the Bienes Comunales. The Canadian company did not acquire the actas of posesión for the land and did not apply to have it rezoned from agricultural to residential use. By reserving a 40-meter-wide strip along the federal zone, the Bienes Comunales is working to ensure public access to its beaches.